The ability to understand one’s immediate surroundings has always been an extremely important skill. For this reason, humanity has spent thousands of years developing and perfecting the craft of representing spatial information including routes or landforms. In today’s age of modern technology, however, the amount and variety of information that needs to be mapped are increasing. Nowadays the ability to have a grasp on our surroundings is proving more complex. This reading list will therefore explore how cartography turns out to be useful to facilitate knowledge exchanges and how it can serve as a vehicle for critical thinking.

Explaining Cartography

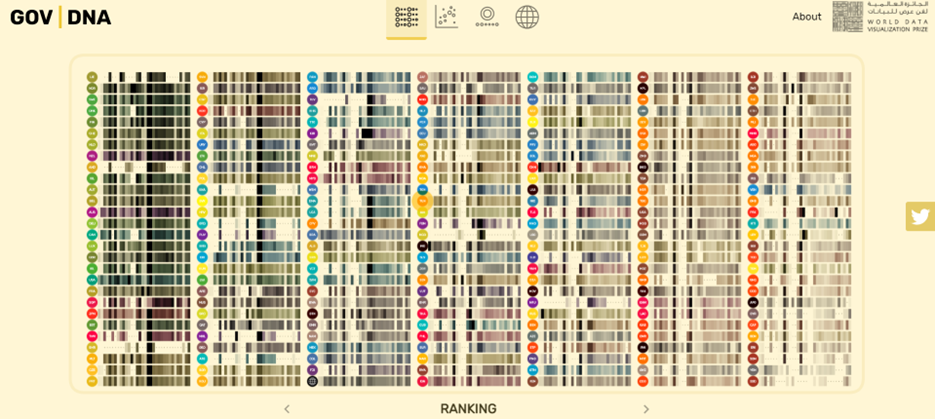

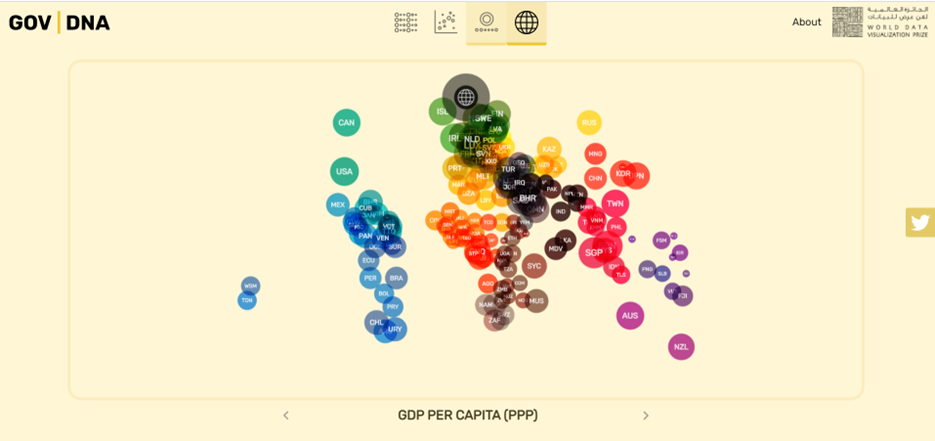

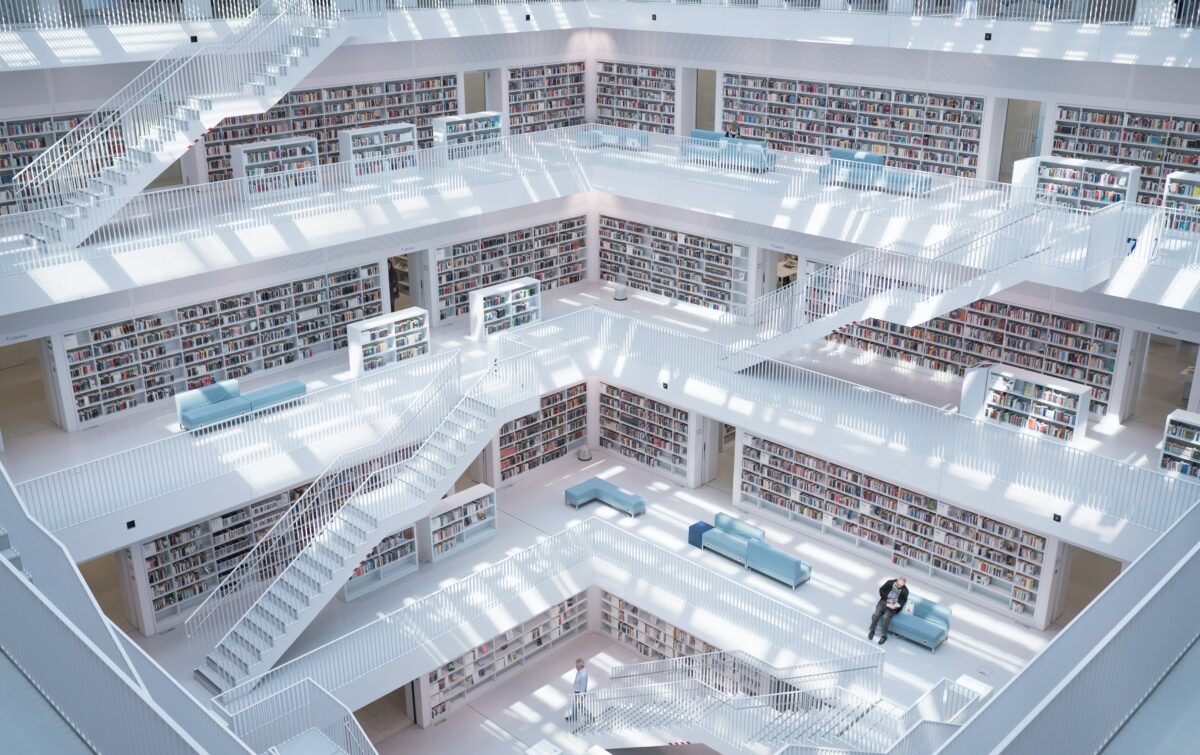

Cartography is the practice of map-making. Originally cartographers graphically represented spatial or geographical data but are now faced with having to translate diverse figures from multiple sensors and multiple origins. According to Elik Eizenberg in Forbes technology online magazine, we find ourselves swimming in data (and should care about it). As we can’t fully harness all data, the data scientists’ continuation of collecting new data, slowly loses meaning. Mapping, Georg Gartner argues in an article for Ersi, the global leader in geographic information systems, bridges between human users and all this data. It uses visualization to make science approachable to the public, fully unleashing its potential.

From Knowledge Reception to Knowledge Exchange

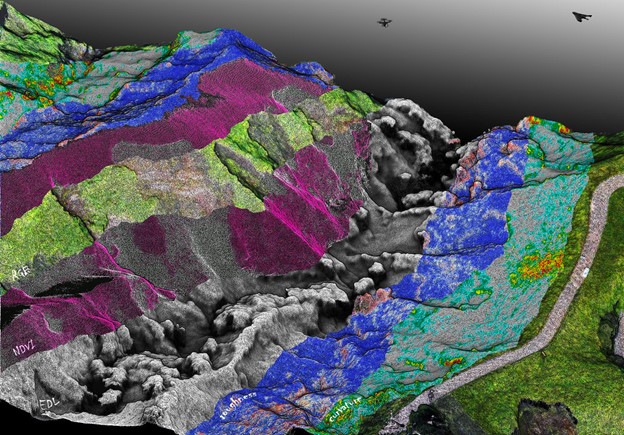

Empowering citizens to make informed decisions can also have another effect, namely mutual information exchange. Originally cartographers collect data from various measuring tools such as aerial photographs, remote sensing, field observations, or coordinate lists. This data, however, as mentioned by Horizon 2020-funded WeObserve, has a scarce update date due to increased costs and timely data validation procedures. Today, considering the increased complexity of data, cartographers also turn to alternative sources such as citizens.

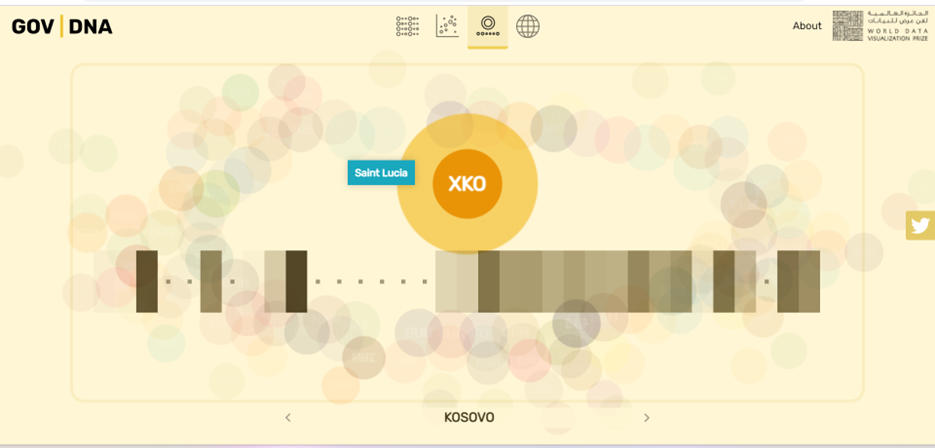

According to Caroline Anstey for The New York Times, this new shift towards crowdsourcing information is immensely useful to cartography. Citizens provide both quantitative, but also qualitative data often omitted by cartographers. The citizens’ expertise comes from living in one place for a prolonged period of time. Changes in demographics, environment, human relations, or even housing habits are useful to mapping projects as they can translate into policies or planning decisions. To build trust underlying this exchange, cartographers should provide citizens with clear and understandable information.

Cartography as a Vehicle for Critical Thinking

According to Sukhmani Mantel for The Conversation, visually mapping relations allows information to engage multiple senses and become relevant to daily life. And indeed, citizens are able to handle novel concepts with an extensive social and cross-cultural understanding. This is what Aleks Buczkowski explains in his piece written for GeoAwesome, the world’s largest geospatial community.

Essentially, Stevenson et al., from Stockholm Environment Institute, claim in an SEI Brief about extreme citizen science approaches in digital mapping, that people from mapping practices, no matter their education level, gain the ability to understand the developing world. This supports their chances to better participate in it also on a more general level: previously excluded groups become aware of how they can co-create and get involved. They now contribute to scientific research, so-called citizen science.

As stated by Fraisl, Heyl, and Hager, researchers at Institute for Applied System Analysis, citizen science is important for the democratization of the scientific field. At the same time, it plays a role in empowering citizens to make informed decisions about their surroundings. This way, as mentioned by Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe, authoritative power becomes decentralized and decision-makers can be held accountable for their actions.

Conclusion

Obtaining accurate cartographic data through crowdsourcing is something that is in its early stages, but is increasingly practiced. Especially because now citizens have increasingly more opportunities to use tools, which give them access to global data. On an entrepreneurial scale, this is already taking place. The Domino-E project, which focuses on developing a federation layer optimising the availability of Earth observation data, builds on interoperability and knowledge sharing. Knowledge sharing generates knowledge creation, which is why it is important for cartographers to bet for information exchange as it benefits both them and citizens equally.