Many tips have been shared over the past weeks and months. This one is the perfect AI for research, and the other is the perfect AI for editing texts. Ideas for the best prompts for semantics-based generative AIs are flooding Twitter, Reddit, and the like. In this Reading List, we don’t want to give tips on which AI can be used for what. For a reading list, that doesn’t make much sense at the moment, not least because of the fast pace of technological development. We also don’t want to report on how AI can have an impact on science communication. We already did that last summer in Reading List #021. Rather, we have collected a few texts on thoughts about how AI could change science in the coming years. Enjoy reading!

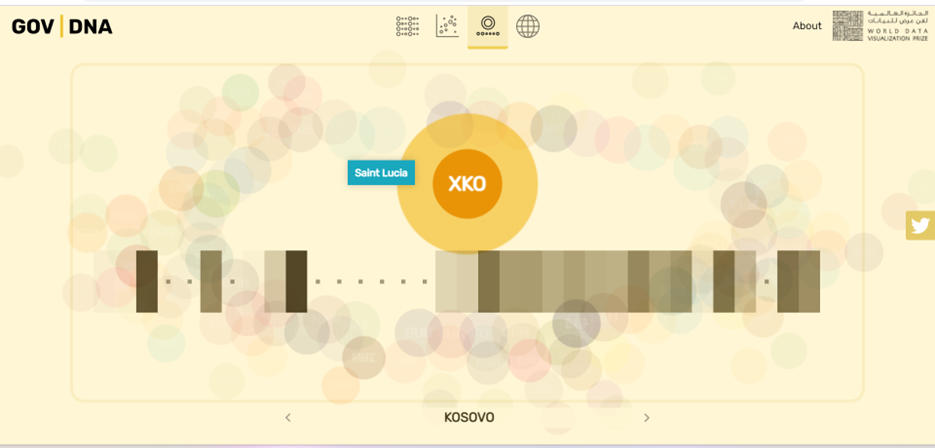

Artificial intelligence with an overview

One of the biggest challenges of science, regardless of discipline, is keeping up with the flood of articles. 70,000 publications deal with the protein p53, according to the think tank Enago. This is the first I’ve heard of it today. Apparently, it is relevant for the early detection of tumors. In 1993, it was voted “Molecule of the Year”. On the occasion of this anniversary, an AI of my choice finds the following review: “The first 30 years of p53: growing ever more complex” by Arnold J Levine and Moshe Oren (paywall). In fact, there are now a number of tools that claim to find articles and present them in their respective publication context. The start has been made.

Disruptive Artificial Intelligence

With the newly gained overview, the quality of results and outcomes can also be reclassified. And this also applies outside of science. In an interview with Digitale Welt, Prof. Mario Trapp, director of the Fraunhofer Institute for Cognitive Systems IKS, remarks: “Even if you can still have the results of AI checked for plausibility by doctors today, this will hardly be possible in the future because of the increasing complexity.” The choice of words is exciting: Trained people can still check the plausibility of results. This will probably no longer be possible for a long time.

As a new key technology with a broad spectrum of applications (even if all references and points of reference so far point to medicine), universities are now facing investment hype for the third time since the 1950s and 1970s. This time, multidisciplinary research in step with action (i.e. industry) and politics is particularly in demand. At least that is the argument of Y. K Dwivedi et al. in an opinion paper published in the International Journal of Information Management. More applied, and with a focus on the extent to which the greatly altered interests brought about by AI interact with media, industry, and research, G. Berman, K. Williams, and S. Michalska argue in their study that research in the field of artificial intelligence functions differently than in other fields.

Proactive Artificial Objectivity

AIs help to keep track of things, they flush new money into the universities’ coffers. Overwhelmed, I return to medicine and to an article from 2018. On the Science Blog – Kaleidoscope for Science, Norbert Bischofberger wrote a fascinating article entitled “With artificial intelligence to a proactive medicine? A question that applies in a modified form to all disciplines today?

At that time, Bischofberger concluded that we might soon no longer “react” but proactively take care of ourselves. Five years later, knowledge production could soon be taken proactively into the hands of AIs. The question is whether an objective understanding of science will play into our hands. We will see.